Feature

A Family’s Legacy, A San Antonio Story

More than 150 years of Carter family stories are coming to life in letters, receipts and diaries

A 19th century home by famed Texas architect Alfred Giles was Marline and Paul Carter’s playground in the 1960s and ’70s. With its piles of dusty, old and unopened trunks in the attic and antique toys dating back to the turn of the century, it was a perfect haunted house for kids with wild imaginations.

Little did the siblings know that 40 years later, the house would become known as San Antonio’s treasure chest for the secrets kept within those dusty, old trunks.

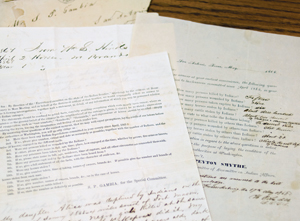

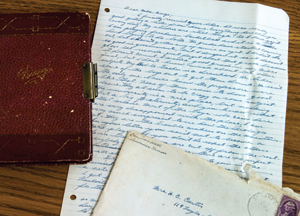

Inside, sometimes on parchment as thin as sewing pattern paper, are thousands of personal thoughts elegantly and carefully scrolled with a penmanship not often seen today. There are letters to brothers, sisters, mothers and fathers, sometimes about a new silk dress or about the death of a family member. There are telegrams, some still tucked away in their original envelopes, sent by sons serving in wars. And there are detailed reports of wives and daughters killed in violent Indian raids.

The Carter family papers are now a permanent part of the Archives and Special Collections at UTSA and are available for free to the public for viewing and research. Already at more than 4,000 pieces, the collection is still growing as the family steadily empties the attic at the historic Maverick-Carter house at 119 Taylor Street.

For generations, the trunks sat untouched and now serve as perfectly preserved time capsules chronicling one family’s life on the frontier in the 1800s and on to the 1990s. More than 150 years of family stories, letters, diaries, photographs and maps were stored away, and they all give insight into one of the first Anglo families to settle in San Antonio, as well as the development of the city itself.

“You’re supposed to go out with the old and on with the new, but this worked out so much better for us…because five generations go by and all of a sudden you actually have this time capsule, and then it’s worth looking back to see how life was in San Antonio,” says Paul Carter. “It lets you peek back in time on how things really were.”

It was that recent realization that prompted the family to donate the papers and create the Carter Family Endowed Library Fund. And the value is immeasurable, says David Johnson, history professor and vice provost for academic and faculty support.

“Many of these documents have not been seen in public for 100 plus years, and they have this immediacy and sometimes poignancy and tragedy that make them extraordinarily attractive as subjects for study.”

The White Angel

The house at 119 Taylor Street sits almost hidden in the midst of modern development. Bracketed by businesses and a downtown parking lot, and across the street from Municipal Auditorium, its pointed rooftop just barely peeks out between surrounding trees and buildings.

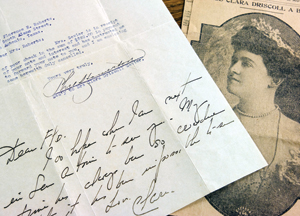

But when Aline Badger Carter and her husband, Henry Champe Carter, purchased the house in 1910 from William Maverick, son of one of the signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence, the San Antonio River cut right behind it. There were no buildings or bright streetlights to obstruct Aline Carter’s view of the planets and stars from the observatory built on the rooftop. That’s where she housed her 1918 telescope, which, for several years, she used to predict eclipses for the local newspaper.

Aline Carter, known as the White Angel of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church because of her trademark white flowing organdy dresses, as well as for her charitable contributions at jails and with orphans, was passionate about learning. She eagerly explored topics ranging from science and poetry to religion. In her house she kept animal fossils and geological specimens, which remain in the attic today.

“She was a scientist and a naturalist,” says Paul Carter, her grandson. “She always thought that science allowed you to discover God’s mysteries.”

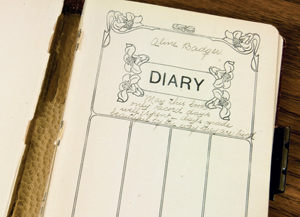

But Aline Carter is perhaps best known as Poet Laureate of Texas from 1947 to 1949. A distinguished author, she published two books and, before her death in 1972, was working on a thousand-page historical fiction novel about the life of her grandmother, Sarah Riddle Eagar. The manuscript is part of the collection now housed at UTSA’s archives.

Aline’s husband, a well-known Texas attorney and former president of the State Bar Association of Texas, was 31 years older than his wife. And, as family stories go, they were so deeply in love that they frequently left each other love notes scattered throughout their home. Love notes will also be in the collection.

“We’re collecting them to put on display so people can see what it is like living in a romance novel,” Paul Carter says, quoting from one: “ ‘When I whisper Aline, all the ecstasies of heaven and earth are mine.’ That’s the kind of thing he would leave around the house.”

H.C. Carter died in 1948. Having given much of their wealth to charity, Aline Carter was forced to convert her home into apartments, which she rented out after his death.

After she died, the house sat empty and eventually fell into disrepair. Ceilings leaked. Dust and bugs took over. And throughout, the priceless papers stored away in trunks remained untouched by anything but silverfish in the third-story attic.

“I didn’t think my mother was a materialist enough to save love letters,” says her son, David Carter. He only recently found out about the love letters sent to his mother, whom he and his brothers grew up calling “my angel” in French. And, like his mother, he has a collection of all the letters his wife ever sent. “It’s a problem with the family,” he says about collecting.

But his daughter says the collection has had a huge impact on her. As a teenager, Marline Carter, now Lawson, would sneak glimpses into her grandmother’s old diaries. When she was in her 20s, she pilfered one and read it from cover to cover.

“It opened up a whole new life for me,” she says. “I always looked at them and read them, but it wasn’t until I actually took some things and had a chance to study them that I understood that this is a true piece of amazing history of San Antonio and an interesting woman that was a part of it.”

Paul Carter says he hopes to keep his grandmother’s charitable work, scientific contributions and poetry alive by converting the house into a museum and making his family’s papers available to UTSA for the public.

“She was unique and progressive, so that’s why we want to keep that theme going,” he says. “We’re hoping to perpetuate that and celebrate it.”

Leaving a legacy

Walking in the attic on a recent spring afternoon, Paul Carter picks up a yellowed San Antonio Daily Express from 1888. The pages are intact, though delicate. Illustrated pictures of downtown San Antonio show storefronts that look remarkably similar to today. Newspapers like this one, he says, were strewn haphazardly across the attic floor for decades.

Most families throw away grocery bills as soon as they’re recorded in the checkbook, but the Carter family wasn’t like most families. Bills and receipts from grocery stores, candle makers and the meat market are among their collection. Records like those help reconstruct a neighborhood. Bills have letterheads with the names of companies and addresses that have long been paved over by streets and other modern development.

“That’s the value in these sorts of papers in terms of reconstructing and to understand San Antonio’s history,” UTSA historian Johnson says. “This is the real stuff that makes history vivid.”

Relics like these are rare, he says. As a city, there seems to be a massive historical loss of memory since the Battle of the Alamo. What records do exist are scattered among various archives throughout the state. But in this one attic, he found a treasure he only hoped existed before.

“I have always said this city is probably full of attics full of family papers, and nobody is doing anything with them,” he says. “I walked into the Carter family’s attic and it was like, for a historian, finding the mother lode. It was just kind of an ‘Oh my God’ moment.”

And now that history is available to anyone who wants to see it. Located at UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures at 851 Durango Blvd., the Archives and Special Collections officially opened in 1997 and has amassed more than 300 other collections, ranging from Mexican manuscripts from the 1500s to original Fiesta San Antonio Commission photos of the 1920s.

The Archives and Special Collections also serves as the repository for the university’s materials about San Antonio, women and gender, authors and the political activities of the city’s Mexican American community since World War II. Recently, the archives has begun digitizing collections, capturing Web sites and has also released a blog and two Twitter feeds.

Stefanie Wittenbach, assistant dean for collections, and Mark Shelstad, head of the Archives and Special Collections, say as the library’s collections grow, so too does the number of people who use it for research. Last year, the library answered about 800 e-mail requests and nearly 300 people visited the Archives and Special Collections. As recognition of the archives increases, they hope that more San Antonio families will consider donating their original documents to the UTSA Library.

One person’s junk, another’s treasure

In an age of text messages, e-mails and Twitter, people’s lives aren’t written out on notebook paper anymore. Diaries have been replaced by My Space blogs. The use of language has changed. Penmanship has changed. As more information becomes digital, there is less to feel and hold.

“It’s emotional,” says Shelstad about opening letters unread for more than 100 years. “To actually sit down and look at the type of handwriting and feel the paper too, there’s a very textural thing about being able to look at some of these archives. You don’t get that just anywhere.”

And as time goes on, there will be fewer opportunities, Wittenbach fears. That presents new challenges to preserving a family’s legacy.

“I don’t know what will be around to collect in another couple of generations,” Wittenbach says. “Who writes letters as much as we used to? There is going to be less output to try to collect in a physical form.”

And that’s what makes the Carter donation so important, Johnson says. Finding something so intact and far ranging was “kind of like finding El Dorado,” he says of the collection. “It was like treasure hunting, and this really is a treasure.”

Like his ancestors before him, Paul Carter keeps everything. Take his first cell phone, so big it resembles a field World War II radio. Instead of being nestled in a dusty trunk on the third floor of his grandparents’ home, he keeps it in a barn. The horses are long gone. Stacks of other collectibles like the phone surround his first car, a 1960 VW Beetle.

“It’s like I just can’t let it go,” he says. He used to feel guilty about it. He used to think eventually he’d get to throwing everything away. But now, he says, he feels justified in being a pack rat.

“Sadly, [the reaction to his family’s papers] is reaffirming and it’s making me worse,” he says. And so, “The theme continues. And there will be somebody coming down the line that says ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so glad you still have that.’ ”

- Lety Laurel

Share this Story

Share this Story

Web Extra

Peek into the Carter's third-floor attic and see what other treasures have been uncovered in a slideshow narrated by Paul Carter.

UTSA librarian Mark Shelstad talks about what the Carter collection reveals about life in San Antonio more than a century ago.

We'd love to hear from you

Use this form to share your thoughts.