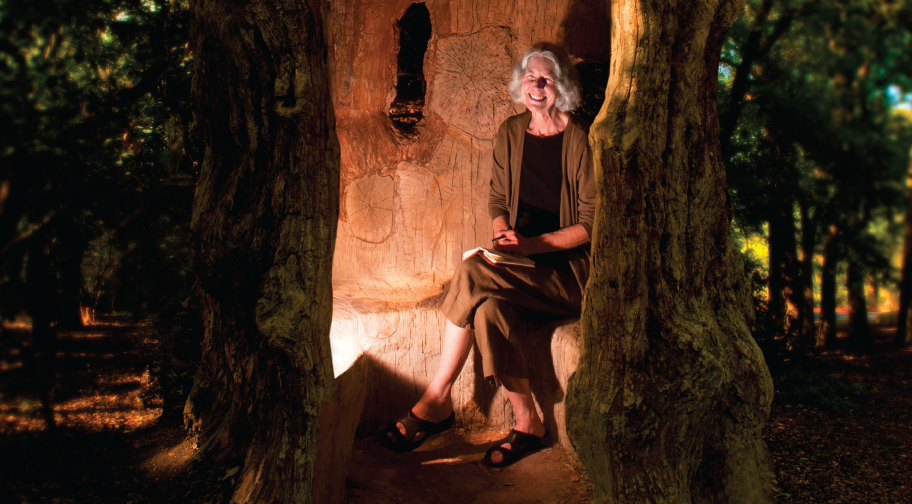

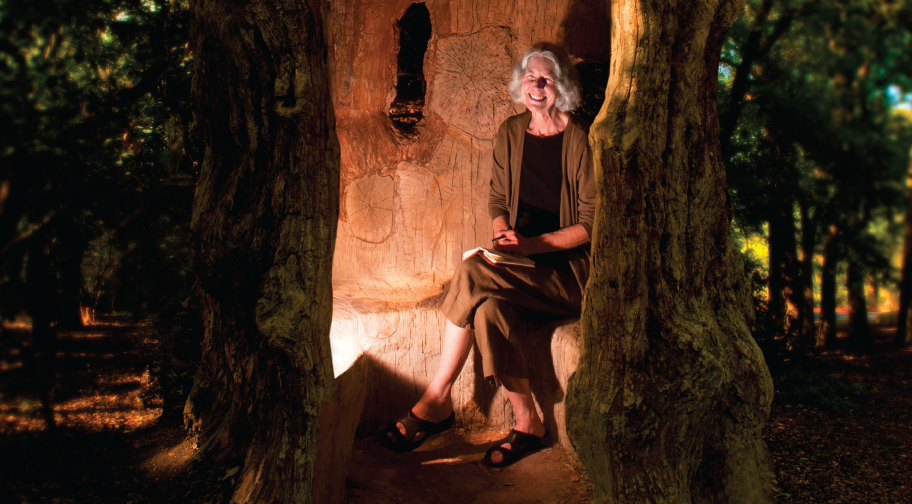

For Wendy Barker, the beauty and profound depth of poetry begins when we’re children. No, she takes that back. It begins even earlier–in the womb.

"As tiny beings inside our mothers, we hear that heartbeat, those gurgles, our mother’s voice," said Barker, a professor of English and UTSA’s poet in residence. "All those pulses and sounds we live with for nine months. The origin of poetry goes back to the womb."

Poetry has been central to Barker’s existence, so much so that she can’t imagine a life without it.

Yet, like the rest of us, Barker lives in a world of iPads, smartphones, Wi–Fi, Xbox, Skype and neverending hype on the latest electronic gadget. It’s a world driven by technology and all manner of scientific inquiry and discovery. In such a world, can the somewhat quaint, romantic notion of poetry survive?

Indeed, explained Barker. It can even thrive.

"Poetry’s never going to die as long as we’re creatures with heartbeats," said Barker, who earned her doctorate at the University of California, Davis.

She likes to quote the 20th-century American poet William Carlos Williams, who said, "It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there."

Born in New Jersey but raised in Arizona, Barker grew up to the sounds of poetry.

"My mother and father read A.A. Milne’s poems to me from the time I was a toddler—When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six. The delight in the play of the language in those poems never left me."

When she was older, her father would read poems out loud after dinner. Robert Frost was a favorite.

But poetry is much more than pretty words, said Barker, author of hundreds of poems and a dozen books and chapbooks.

"Frost once said ‘Poetry is a way of taking life by the throat,’ " she said. It can also heal, she added.

"‘Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood,’ as T.S. Eliot said. It can make us aware of ‘unnamed feelings.’ He wanted a poem to come from the deep emotional core of the writer to reach the deep emotional core of the reader or listener," Barker said. "When we write from that deep emotional core, we are writing from our soul. From the deepest part of ourselves, which is also maybe the highest part. I’ve seen poetry connect people as profoundly as music can."

But poetry tends to intimidate a lot of people these days, Barker acknowledged. Perhaps it’s seen as elitist or inaccessible.

One reason, she said, is that some of the great poets from the early 20th century, like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, "were consciously trying to write poetry that did not appeal to the masses. They were tired of the easy rhymes and sentimental verse popular in the late 19th century. They were trying to write something new that reflected the age in which they lived.

"Now, today, many of us can look at their poems and find that we don’t have as much difficulty with them as people at the time did, because somehow our sensibilities have caught up. But their flagrant determination to flaunt their stuff without any regard for popular taste caused a lot of people to turn off to poetry."

Moreover, she said, a national and natural poetic disposition is impeded by a culture that mainly values material wealth.

From the very beginning of this country, from our Calvinist ancestors, she said, the arts were seen by many as a waste of time, not worthy of a people who needed to be doing "real" work.

"There are other cultures where leaders of governments are poets," Barker said. "Throughout South America and Europe, poetry is far more valued than it is in the United States, where it’s, ‘How much money do you make?’"

When people say they don’t read poetry or care for it, "I don’t think they really mean it," Barker said. "People who say that have been taught poetry poorly."

A good poem, she’s fond of saying, "should hit you in the gut... before you even start thinking intellectually about it."

And while she once taught high school and middle school and calls public school teachers "incredibly burdened" and even "heroic," she believes that some teachers just aren’t comfortable with poetry.

"So, rather than reading a poem out loud, just reading it and letting the words catch fire, the way you listen to music—you don’t listen to a song and then immediately dissect it—the students are given the poem only in writing and they’re asked to puzzle it out," she said. "That can take the joy out of it."

Even in her classes now, Barker said, she fights the concept of poetry as a problem to be solved.

"One of the things I was struggling against in a class recently was the desire of many students, when confronting a poem for the first time, immediately to try to analyze it," she said. "I always want to start by letting a poem wash through you. Let it have its effect. Relish it. Then, of course, our curiosity leads us to want to understand how the poem creates its effect on us."

Not surprisingly, Barker believes that poetry "is an integral part of the university’s mission," not just because it’s the oldest of the verbal art forms "but because it is so vital and vibrant."

It’s at least as important as studying biology, she said.

"Once somebody asked what I wrote. When I said poetry, he said, ‘Oh, fluffy stuff.’ No, it’s not fluffy stuff. If it’s working, it hits us deep down, where we live."

–Joe Michael Feist

Sombrilla Magazine: Who do you write poetry for?

Wendy Barker: I don't write with a particular reader in mind, but I do not want my poems only to reach other poets. I'd die happy if I felt that my poems were respected by the best poets but also moved folks who don't write themselves.

While working on a poem, I don't think of audience, but of the voice from which the poem needs to speak, the place from which the poem needs to grow. Each poem will have its own diction and syntactical patterns, as well as its own kind of music and use of poetic devices (like metaphor), and the work is to find what each particular poem needs to do. But I always try to make sure that a poem reaches beyond a strictly academic readership.

SM: Where/when do you write? Do you journal in verse? Do you write on paper or computer? Any rituals to writing?

WB: I write whenever I can. I don't have a regular schedule. I'm not one of those writers who writes from, say, 8 to 12 every day. But I write regularly and rigorously. Sometimes I'm working on a draft while also doing laundry and getting up from time to time to put clothes in the dryer. Often I go back to a draft many times during a day and evening. I revise obsessively. I'm always working on a poem, or several poems, even in my head while I'm doing chores or driving.

I do take notes frequently in a journal, and sometimes jot a first draft in handwriting. But always the real work is on the computer.

No rituals. I just write. Whenever I can. Sometimes I'll be working on a poem and not realize that four or six hours have gone by.

SM: What was the first poem you memorized?

WB: I think the first poem I learned "by heart" was Robert Frost's Stopping By Woods.

SM: Who is your favorite classic poet and why? Your favorite emerging poet?

WB: There are too many to name. Keats, Browning, Dickinson, Whitman, Donne—and if we can move to the 20th century, William Carlos Williams, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, Theodore Roethke—so many, so much richness.

Emerging? Or contemporary? Again, so many. Here in San Antonio, Barbara Ras. And my wonderful colleagues at UTSA. And David Kirby, Barbara Hamby, Denise Duhamel, John Koethe, Tony Hoagland, Alicia Ostriker, Ruth Stone and many, many more.

SM: Whose poetry do you read for comfort? For inspiration?

WB: I don't read for comfort, but if I need to be calmed, I'll go to Matsuo Basho, Marisa Bisson or Kobayashi Issa. Also, I love to read poems by poets writing in languages other than English. Though I'm pretty much monolingual, I love reading poems in translation with the original version alongside. Celan, Rilke, Montale, Neruda, Paz, Juarroz. Something about getting out of my own language and into another as best I can provides a way of opening into all kinds of possibilities.