ORIGINALLY POSTED 02/16/2017 |

FROM THE Spring 2017 ISSUE

Groundbreaking discoveries in cancer research this past year have showcased the intensive efforts of UTSA faculty and students to combat the disease. From professor Matthew Gdovin’s innovative new method to kill cancer cells to the nearly $4.6 million grant awarded to the Center for Innovative Drug Discovery to find more effective cancer drugs, university researchers are making international news with their successes. And they show no signs of slowing down.

But beyond the headlines, there is an undercurrent of research and innovation across UTSA’s campuses that’s focused on cancer—the second leading cause of death worldwide.

Cell Self-destruction

Biology professor Matthew Gdovin had spent nearly two decades researching the human respiratory system when a query from a student led to a shift in perspective: What if you could make cancer cells kill themselves? It was, Gdovin had to admit, an excellent question.

He’s since developed a method that involves injecting a chemical compound into a group of cancerous cells that diffuses into the tissue. He then aims a beam of light at the cells, which activates the compound, causing the cells to become very acidic inside. Overwhelmed by the acidity, the cells self-destruct. Within two hours of the treatment, Gdovin estimates that up to 95 percent of the targeted cancer cells will be dead.

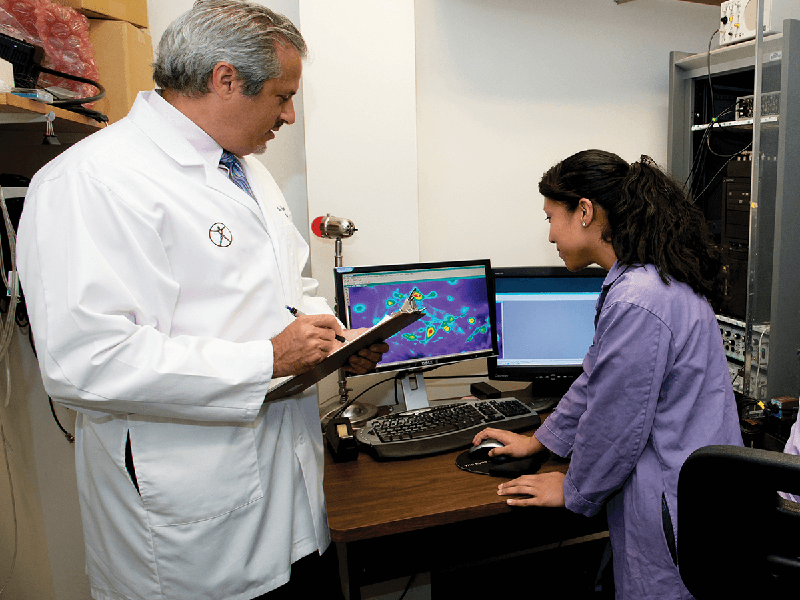

Matthew Gdovin has developed a promising, noninvasive procedure targeting breast cancer.

Matthew Gdovin has developed a promising, noninvasive procedure targeting breast cancer.

In the past two years he’s advanced his photodynamic cancer therapy, originally reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, to the point that it’s noninvasive, requiring just an injection of nitrobenzaldehyde fluid followed by a flash of ultraviolet light to cause the cancer-killing reaction. Gdovin has begun to test the method on drug-resistant cancer cells to make his therapy as strong as possible. He’s also started to develop a nanoparticle that can be injected into the body to target metastasized cancer cells. The nanoparticle is activated with a wavelength of light that can pass harmlessly through skin, muscle, and bone.

Gdovin tested his photodynamic acidification method against triple negative breast cancer, one of the most aggressive types of cancer and one of the hardest to treat. The prognosis for triple negative breast cancer is usually very poor. After one treatment in laboratory testing, he stopped the tumor from growing and doubled the chances of survival in mice.

Gdovin hopes that his noninvasive method will help cancer patients with tumors in areas of the body that have proved problematic for surgeons, such as the brain stem, aorta, or spine. It could also help people who have received the maximum amount of radiation treatment and can no longer cope with the scarring and pain that goes along with it as well as help children who are at risk of developing mutations from radiation as they grow older.

The work has also made a difference to Gdovin’s students who assisted him in his research. “The fact students were so involved is part of the joy of it,” he says. “You shouldn’t underestimate what they can bring to research. Sometimes it takes someone young, someone unaffected who’s just looking at the problem from a new angle.”

I Want a New Drug

Cancer killed three of Doug Frantz’s uncles. Stanton McHardy lost his father and sister to the disease. Now the two UTSA chemistry professors are working to discover cancer treatments at the Center for Innovative Drug Discovery, a joint venture between UTSA and The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“We’re not just studying existing cancer drugs,” says McHardy, the CIDD’s codirector and also its Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker medicinal chemistry core director. “We’re designing and creating novel molecules that can be designed and engineered to treat cancers from multiple biological pathways. It takes a collaborative team at both UTSA and UT Health San Antonio to be able to do that.”

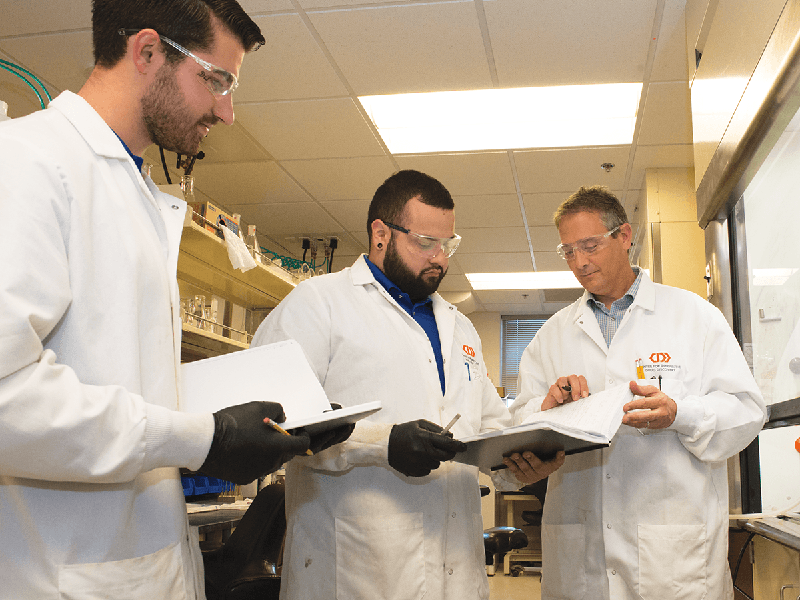

Stanton McHardy (right) leads the UTSA Center for Innovative Drug Discovery, studying new cancer treatments.

Stanton McHardy (right) leads the UTSA Center for Innovative Drug Discovery, studying new cancer treatments.

In August the center received a nearly $4.6 million grant from the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas. McHardy is the principal investigator on the grant, which will support the center’s ongoing research in the preclinical stage of small molecule cancer drug discovery as well as provide opportunities to develop new cancer therapeutic programs. The CIDD will also continue to focus on programs that target triple negative breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and brain cancer.

Frantz, the Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker distinguished professor in chemistry, is leading a team of UTSA students in chemical biology research. Because stem cells can become any type of cell in the body, Frantz’s laboratory is focused on identifying molecules that can convince stem cells they want to become something other than cancer. Frantz’s and McHardy’s research in this area are very synergistic with the PriStem initiative and stem cell research for cancer and regenerative medicine that’s ongoing at UTSA.

Doug Frantz is working to prevent stem cells from wanting to become cancerous.

Doug Frantz is working to prevent stem cells from wanting to become cancerous.

With the CPRIT funds, the center will be able to venture further into discovering novel compounds for multiple types of cancers and expand the CIDD’s cancer program portfolio. According to McHardy, what differentiates the research at the center from that at other universities is the developmental mentality. “We would ultimately love to see intellectual property come out of here that’s going to benefit patients,” he says, ”and spin out to become companies.”

Connecting More Dots

Research at the university isn’t limited, though, to the more obvious science and engineering disciplines. For example, under the direction of UTSA College of Education and Human Development kinesiology professor Meizi He, the Building a Healthy Temple Cancer Primary Prevention Program partners with local churches to help people live healthier lives. The program targets three modifiable risk factors—poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and obesity—by educating church congregants and their families. Additionally, the program uses the train-the-trainer method to enable community residents to carry on educating their neighbors, which ensures the program’s sustainability after implementation.

Additionally, in the College of Liberal and Fine Arts, communications professor Kimberly Kline studies cultural sensitivity around health issues in the popular media. “For instance,” she says, “my colleagues and I noticed there had been an upsurge in reports of side effects from the HPV vaccine. Our study suggested that the upsurge could have been related to the heavy public debate regarding the vaccine. In other words, it appears that public discourse in the mass media can influence health promotion efforts.”

Kline is also a consultant for a CPRIT-funded Baylor College of Medicine initiative to develop culturally appropriate educational videos to be shown in health clinics. The videos will encourage English-speaking African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Caucasian parents to talk to their health care providers about having their children vaccinated against HPV.

And in UTSA’s College of Public Policy, demography professor Corey Sparks is conducting research to find cancer hot spots in Bexar County and South Texas using demographic and environmental risk factors. One of these hot spots—or a cancer cluster—occurs when a greater than expected number of cancer cases among a group of people in a defined geographic area over a specific time period, according to the National Cancer Institute.

“This information has an application because people in county health departments are going to be interested in knowing what we have in our backyard, whether we have a level of cancer that is four to five times the level that should exist, and what is causing that,” Sparks says. “What I expect is a lot more questions. The first goal is to identify where these places are and then to focus on specific hot spots and learn as much as we can about these places.”

Cancer research has come a long way in recent decades, says Bernard Arulanandam, UTSA’s interim vice president for research, but he adds that such a persistent disease requires more work. UTSA, he stresses, is ready to meet the challenge: “We are committed to world-class research that improves quality of life. We are equally passionate about training the next generation of brilliant cancer researchers.”