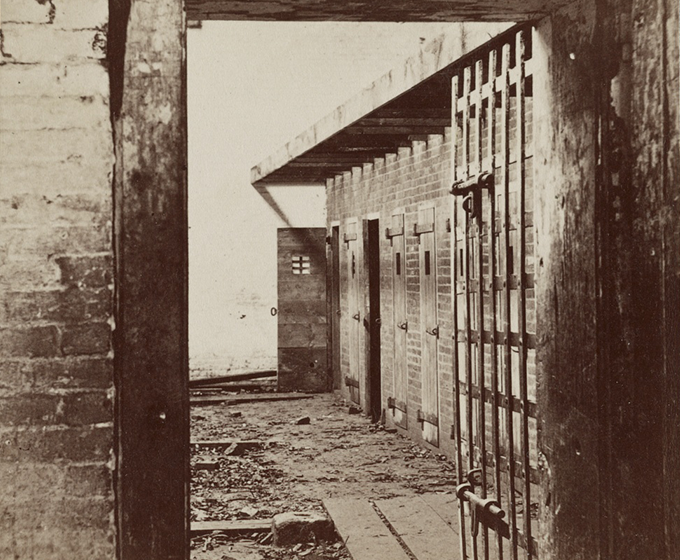

This slave pen was photographed in Alexandria, Va., between 1861 and 1865. (Photo: Library of Congress)

FEBRUARY 4, 2021 — To answer the call to address social justice, Crystal Webster, an assistant professor in the Department of History at UTSA, has incorporated into the academic curriculum a graduate course offered to doctoral students called U.S. History: Race and Incarceration. In the course over 20 students examined the formation of the American carceral state, from the birth of the penitentiary in the 1900s to the rise of mass incarceration today.

Visiting participants included acclaimed historians and authors of assigned books from leading institutions such as Jen Manion (Amherst College), Carl Suddler (Emory College), and Lindsey E. Jones (Brown University), who led in-depth discussions.

The books discussed included Liberty's Prisoners; Presumed Criminal; and The Most Unprotected of all Human Beings: Black Girls, State Violence, and the Limits of Protection in Jim Crow Virginia.

One of these participating doctoral students, Karyn Hixson ’24, connected with UTSA Today to discuss the course and why she thinks it’s important to enroll in these innovative seminars.

Would you describe what you learned about some of the origins of this specific carceral culture and how it developed in the U.S.?

There was a loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment which dictated that slavery was abolished except for those that committed crimes, so Blacks were arrested for petty crimes or vagrancy, and mainly applied to those that didn’t work on farms as sharecroppers or refused to sign yearly labor contracts. Later, with the second rise of the Industrial Revolution, the need for cheap labor in the 19th century led to African Americans being arrested and placed in prison. The penal institution would then lease these same prisoners to corporations for cheap hard labor—in essence, working for the ruling class for free.

In your final analysis for this class, you applied the term “decades of brokenness” to the African American experience. Would you explain this further and how it relates to carceral history?

Just a little over a decade ago, researchers Bruce Western and Christopher Wildeman described the mass incarceration system and its long-term adverse impact on the achievable economics and equity for this group. Specifically, they studied how the large amount of fees incurred by going through the justice system and the permanent felony records keep ex-convicts from gainful employment. This continues the circle of crime and felons remaining under the control of the penal system. It’s almost a predestination to a life outside of the law.

A house needs a firm foundation to stand and so does the family. Because the African American family has been dismantled first by slavery and now through mass incarceration, “equal justice for all” is difficult to achieve. With my research, the argument is that how the African American family has been systematically torn apart shatters hope for equality and economic justice. How can they, the economically burdened, appreciate the freedoms given and how do the inexperienced become knowledgeable enough to make the jump to financial and social stability?

Can you describe the data or trends that show over-policing leading to the growth of today’s mass incarceration?

Research studies have shown that African American men are incarcerated at levels disproportionately higher than they were 25 years ago. The incarcerated population in the United States has risen dramatically from 300,000 to more than 2.3 million; most of which is due to non-violent drug offenses.

Moreover, according to the 2019 statistical report for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, African Americans represent about a third of those incarcerated yet only 12 percent of the entire state’s population. The same trend is seen nationwide. Imprisonment is not applied equally. For example, in the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, African Americans and whites use drugs at similar rates, but incarceration rates of African Americans for drug charges is almost six times that of whites.

Even in the 21st century, the stereotypical assumptions of Black guilt and white innocence are prevalent. For example, take the recent case of Christian Cooper, the African American bird watcher who was falsely accused by a white woman, Amy Cooper, in Central Park.

What can academic institutions and future historians do to change the discourse on how we face the call for racial justice?

Many beyond the African American experience express astonishment at the unfaced history, particularly the violent racial origins of modern incarceration and over-policing. Cases such as Trayvon Martin, the teen who was murdered just for walking down the street, and later George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, show that aggressive policing is part of a larger arc of history and we need to confront it. Academia can empower Americans to develop skills to understand the systemic forces and institutionalized practices which impact the daily lives of the “other.”

With a history that truly reflects a complex American cultural experience, we can finally begin to ask, "How can we change this?" How can we achieve that true equity we were promised in the Constitution?'

UTSA Today is produced by University Communications and Marketing, the official news source of The University of Texas at San Antonio. Send your feedback to news@utsa.edu. Keep up-to-date on UTSA news by visiting UTSA Today. Connect with UTSA online at Facebook, Twitter, Youtube and Instagram.

Move In To COLFA is strongly recommended for new students in COLFA. It gives you the chance to learn about the Student Success Center, campus resources and meet new friends!

Academic Classroom: Lecture Hall (MH 2.01.10,) McKinney Humanities BldgWe invite you to join us for Birds Up! Downtown, an exciting welcome back event designed to connect students with the different departments at the Downtown Campus. Students will have the opportunity to learn about some of the departments on campus, gain access to different resources, and collect some giveaways!

Bill Miller PlazaCome and celebrate this year's homecoming at the Downtown Campus with food, games, giveaways, music, and more. We look forward to seeing your Roadrunner Spirit!

Bill Miller PlazaThe University of Texas at San Antonio is dedicated to the advancement of knowledge through research and discovery, teaching and learning, community engagement and public service. As an institution of access and excellence, UTSA embraces multicultural traditions and serves as a center for intellectual and creative resources as well as a catalyst for socioeconomic development and the commercialization of intellectual property - for Texas, the nation and the world.

To be a premier public research university, providing access to educational excellence and preparing citizen leaders for the global environment.

We encourage an environment of dialogue and discovery, where integrity, excellence, respect, collaboration and innovation are fostered.