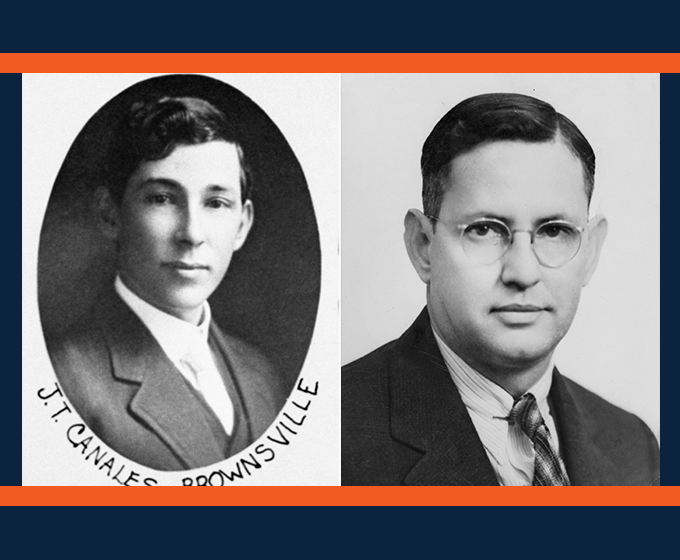

José T. Canales and Carlos Castañeda were trailblazers in Texas history.

OCTOBER 7, 2021 — As part of Hispanic Heritage Month, UTSA Today interviewed Omar Valerio-Jiménez, associate professor of history, on his research and the goal to renew the focus on the lesser-known Hispanic leaders that made valuable contributions to Texas.

You recently published “Refuting History Fables: Collective Memories, Mexican Texans, and Texas History,” what motivated you to research this aspect of history?

While conducting research for my current book on the use of collective memories of the U.S.-Mexican War as a motivation for civil rights struggles, I ran across an exchange of letters between four scholars/activists: Adina de Zavala, Elena Zamora O’Shea, José T. Canales and Carlos Castañeda.

These letters were fascinating to read because these scholars were discussing the way Texas history was taught in schools and its negative effects on Mexican American children. The 1935 exchange of letters between State Rep. Canales and scholar Castañeda was particularly fascinating because Canales was very optimistic that Texas history textbooks would change within five years. As we know from recent news articles regarding the state legislature’s attempts to dictate what school teachers can include about Texas history, the debate about what is included and excluded from textbooks continues today.

In this work, you focused on these two trailblazers, Castañeda and Canales for their contributions to Texas history. Why should students of Texas history learn about these individuals?

Castañeda and Canales are fascinating individuals. Castañeda was a Mexican immigrant from a humble family who enrolled at UT Austin and sought to become an engineer, but later changed his major to history after working as a research assistant for a professor of history. He worked at various jobs to support himself throughout college and to support his sisters because both of his parents had passed away. He became an archivist and eventually a history professor who published many books and articles on borderlands history and the Catholic Church. After becoming a U.S. citizen, Castañeda became more politically active through the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), and also served as a government official in the Regional Office of the Fair Employment Practice Committee.

In contrast, Canales was from a wealthy and landed family in South Texas. He became a lawyer, and later, a state representative from Cameron County. He is well known for launching the 1919 legislative investigation into the abuses of the Texas Rangers on the Mexican American community in Texas during the so-called Border War of 1915-1916 and in the decades prior.

These two Hispanic leaders also were motivated by identity politics. They addressed issues of identity based on the relationship between what it meant to be Mexican Texan, Tejano, American and the issue of Whiteness. At the time, this was contentious among Latino leaders in Texas and created divisions. Could you explain how these different identities were used to create inclusion and rights?

Mexican Americans became the nation’s first Latinos after they were incorporated into the nation as citizens in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the U.S.-Mexican War. After the war, approximately 100,000 former citizens of Mexico who lived in the territories acquired by the U.S. became citizens. In the mid nineteenth century, only peopled considered to be white could become U.S. citizens according to the 1790 Naturalization Act.

So, when Mexican Americans became U.S. citizens by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they were legally classified as white as well. However, the reality was much different as most white Americans did not respect the citizenship rights of Mexican Americans nor treat them as white. But a few Mexican Americans did obtain the privilege of U.S. citizenship and whiteness, and these were mainly wealthy Mexican Americans and those who had become professionals. Because most Mexican Americans were not able to exercise their citizenship rights, various civil rights groups, including LULAC, sought to pressure municipal, state and federal officials to respect the citizenship rights of Mexican Americans.

Unfortunately, some of these groups sought to distance themselves from other oppressed groups, such as African Americans, because members believed themselves to be white and argued that associating with African Americans would hurt their civil rights struggles. So, citizenship and whiteness (at least the legal claim to whiteness) served as a barrier to alliances with African Americans and other people of color.

Castañeda and Canales were optimistic that the contributions of Mexican Texans would be included in the role that Tejanos played in Texas’ independence. Currently, has this prediction played out in the history books?

No, very few residents of Texas know the history of Tejanos in the state’s independence movement. For example, few state residents know the significant role of Erasmo Seguín, and his son, Juan Seguín, in helping Moses Austin and his son, Stephen F. Austin, learn Spanish and understand Spanish and Mexican laws. Seguín fought on behalf of Texas independence, and later became mayor of San Antonio in the 1840s. But he was chased out of town by death threats from Anglo Texan vigilantes who objected to Seguín’s efforts to protect Tejanos from Anglo Texan squatters.

He ended up fleeing to safety in Mexico. Seguín was the last ethnic Mexican to serve as mayor of San Antonio until Henry Cisneros was elected mayor in the 1980s. So, no ethnic Mexican served as mayor of San Antonio for close to 140 years. Another example is that of Lorenzo de Zavala, who was originally from Yucatán, but later came to Texas, signed the Texas Declaration of Independence along with several Tejanos, helped draft the first constitution of Texas and served as interim vice president of the Republic of Texas.

You write a great deal on the importance of “counter memory.” Can you describe what this means in connection to the scholarship of history and the importance of celebrations during Hispanic Heritage Month?

I use the term “counter memory” to refer to efforts of Tejanos to create a new narrative of the past that includes their stories. Mexican American scholars and activists sought to create a new, more inclusive history that included Tejanos. They often relied on the collective memories of Tejanos’ roles in the state’s history that they had learned from their families. As part of their efforts, scholars and activists also sought to preserve historical sources related to Tejanos’ roles in the state’s history because they understood that these sources would be important for future revisions of history that were more inclusive.

How does a fable become a part of history? What is one fable that has appeared in the history books?

Fables become part of history when powerful groups and those writing history characterize the fables as true. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the Texas Rangers have been characterized as a law enforcement group that protected the state’s residents against criminals. However, for many Tejanos, the Rangers were seen as an oppressive military force that often abused and terrorized Tejanos to keep Mexican Texans from voting and from exercising their rights. The 1919 Canales investigation into the abuses of the Texas Rangers has recently received more scholarly attention and hopefully will influence future history textbooks.

What is the future of Hispanic Heritage Month in Texas?

As a historian, I would like Hispanic Heritage Month to emphasize the history of Mexican Americans and other Latinos in the state’s history. I would like the UTSA community to learn more about the significant roles that Latinos have played in the development of the state, the challenges they have faced and the successes they have achieved. But more importantly, I would hope that students learn more about Latinos beyond the most well-known names such as Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. They were very important labor leaders. However, students and residents should also learn about historical figures like labor leader Emma Tenayuca, journalist Jovita Idar, historians and teachers Adina de Zavala and Elena Zamora O’Shea, lawyer Gus García, and school teacher José de la Luz Saenz.

UTSA Today is produced by University Communications and Marketing, the official news source of The University of Texas at San Antonio. Send your feedback to news@utsa.edu. Keep up-to-date on UTSA news by visiting UTSA Today. Connect with UTSA online at Facebook, Twitter, Youtube and Instagram.

Move-in Day is an exciting time for incoming students. Students living in Chaparral Village move in from August 20-21. The UTSA Housing and Residence Life (HRL) team looks forward to welcoming you all and helping you settle into your room.

Chaparral VillageMove-in Day is an exciting time for incoming students. Students living in Laurel Village move in on August 22. The UTSA Housing and Residence Life (HRL) team looks forward to welcoming you all and helping you settle into your room.

Laurel VillageThe College of Sciences welcomes our newest Roadrunners to UTSA at VIVA Science! This interactive event connects students with faculty, staff, student leaders, and peers while highlighting the opportunities available across the College.

Outdoor Learning Environment 2 (OLE), Flawn Building, Main CampusWe're excited to welcome the new class of UTSA College of Liberal and Fine Arts (COLFA) students to campus! Move In To COLFA is strongly recommended for new students in COLFA because it gives you the chance to learn about the Student Success Center, learn how to do college successfully and meet new friends.

Galleria (MH 2.01), McKinney Humanities Building, Main CampusBuild connections with your Alvarez College of Business peers and learn more about the Career Compass program! This opportunity will provide fun interactions, giveaways and a chance to meet your next friend!

Richard Liu Auditorium (BB 2.01.02,) Business Building, Main CampusCelebrate the end of summer and the start off a great fall semester with The Housing Block Party! This event will have live music, carnival-style treats, artists, games, and activities galore. Come and join us for a night of fun!

Multipurpose Room/Lawn, Guadalupe Hall, Main CampusBe part of an unforgettable night as SOSA takes the field for its first public performance of the season! Experience the power, pride, and pageantry of UTSA’s marching band. Learn beloved traditions, practice cheers, and feel what it means to be a Roadrunner.

Campus Rec FieldsThe University of Texas at San Antonio is dedicated to the advancement of knowledge through research and discovery, teaching and learning, community engagement and public service. As an institution of access and excellence, UTSA embraces multicultural traditions and serves as a center for intellectual and creative resources as well as a catalyst for socioeconomic development and the commercialization of intellectual property - for Texas, the nation and the world.

To be a premier public research university, providing access to educational excellence and preparing citizen leaders for the global environment.

We encourage an environment of dialogue and discovery, where integrity, excellence, respect, collaboration and innovation are fostered.