Sombrilla Magazine covered the historical impact of HemisFair '68 on San Antonio and UTSA as well as the Institute of Texan Cultures' 40th anniversary celebration of the world's fair.

Introduction to the World

Part of UTSA’s roots lie in HemisFair ’68, the world’s fair that helped put San Antonio on the map

[ This article was originally published in Sombrilla Magazine, Spring 2008 ]

HemisFair, which opened on April 6, 1968, two days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., drew participants from more than 30 countries and brought in performers such as Louis Armstrong, Bill Cosby, and Pat Boone. The event lost $5.5 million by the time it was over, but the civic leaders who organized the exposition say it forever transformed the city’s worldview—as well as the world’s view of San Antonio.

Today [in 2008], those leaders celebrate the 40th anniversary of HemisFair with nostalgia and pride, looking back on it as the defining event that finally brought San Antonio into the 20th century. Some are also looking forward with hope that today’s civic leaders can revive the stripped-down 96 acres where the fair took place and bring HemisFair Park into the 21st century.

UTSA’s Institute of Texan Cultures, which was created during HemisFair as the Texas State Exhibits Pavilion, opened a retrospective exhibit of the event on April 6, exactly 40 years after the fair’s opening day. The exhibit is titled “HemisFair 1968: San Antonio’s Introduction to the World.”

April 6, 1968

During the hours following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination on April 4, union contractors and HemisFair organizers were still laying grass and making arrangements to open the fair. They were determined to continue, despite calls for postponing the opening to allow time to mourn the death of the civil rights leader.

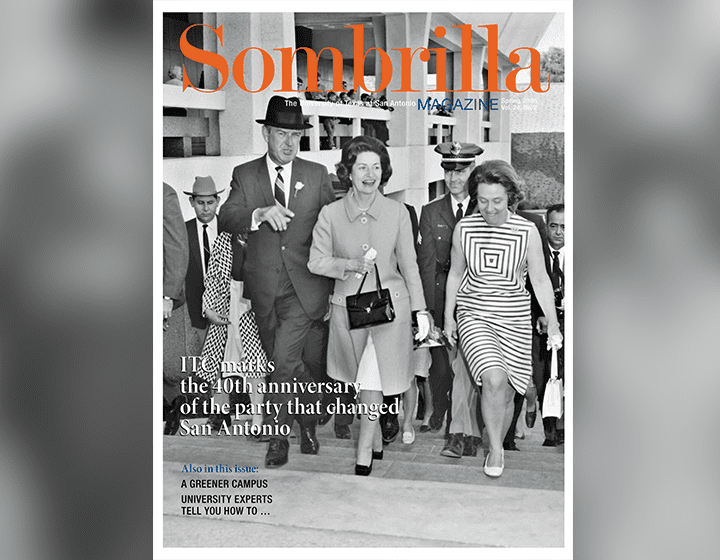

Plans went ahead as scheduled. On opening day Lady Bird Johnson was the featured speaker. Like her husband, Lady Bird Johnson had received death threats from segregationists during what had become a turbulent time in America. Surrounded by federal agents—and with protesters mourning King’s death not far from the fairground entrance—the first lady told the crowd, “Let us not set the fires of hatred but quench them.… What we have become, we owe to dozens of different peoples.… In these troubled, tragic hours, we need to remember that we are moving forward.”

And with that, the celebration of the world’s cultures—from Argentina to Canada, from Belgium to Thailand—commenced.

The six-month world’s fair, which was timed to coincide with the 250th anniversary of San Antonio’s founding, had something to appeal to every interest. On the evening of opening day, for example, the first lady attended a performance of Verdi’s Don Carlo. Elsewhere, the Mexican Voladores, or the “Flying Indians,” spun around a 114-foot pole, suspended upside down in the air by thick ropes tied around their feet.

A mini monorail train circled day and night around the fairground’s perimeter, while the outdoor elevator on the newly constructed Tower of the Americas lifted passengers more than 700 feet into the sky.

The nation’s most famous entertainers popped in and out for appearances, while the world’s most powerful leaders came to San Antonio to join the celebration.

“It was a heady time. It was an exciting time,” recalls Patsy Steves, whose husband, Marshall Steves, headed the underwriting campaign for San Antonio Fair Inc.

The nonprofit organization raised $7.5 million for HemisFair through local businesses and banks. San Antonio voters had approved a $30 million bond for improvements and extensions to the River Walk and the construction of a new convention center. The Urban Renewal Agency allocated $12.5 million to purchase land and demolish the homes where the fair would take place. State legislators chipped in $4.5 million, and the U.S. Congress appropriated $6.75 million for the fair, according to San Antonio Fair Inc.’s records.

“It was total community support,” says William Sinkin, who built interest in the project after Rep. Henry B. Gonzalez approached him with the idea of a fair that would “find a place in the sun for San Antonio.”

“I think that’s the first time that we’ve ever had that kind of community support, where every facet of the community supported something,” recalls Sinkin, who was a local department store executive at the time. “The Democrats, the Republicans, the wealthy ones, the working man, unions—all were supportive. All of the religions were supportive and the media. All together we created HemisFair with excitement and support. And as I said, that hadn’t happened before and I don’t think it has happened since.”

Sinkin and Patsy Steves were the cochairs for the committee that organized HemisFair’s 40th anniversary celebrations on April 6.

“There was such a great interest at the time of the fair,” Steves says. “And I would love to see the citizens of San Antonio just rekindle some of that.”

HemisFair Today

Soon after HemisFair ended, political leaders and fair organizers disagreed over what to do with the site. The organizers had wanted the proposed UTSA campus to be located downtown on the fair’s property. State leaders had plans to build the university near the Hill Country. When it was clear that the university would not be located at the HemisFair, fences were installed around the fairgrounds.

“The city sort of marked it away and let the waterways dry up and become soiled,” Sinkin says. “It was a degree of neglect that hurt that area for years. And gradually people began to use it again. But it was so distressing.” Steves says she would like to see lighted paths, street performers, and the renovation of the Women’s Pavilion on the HemisFair Park property. “You know it’s a wonderful, big bit of real estate. And now it needs to be used well and wisely,” she says.

Urban design consultant Sherry Kafka Wagner puts it another way: “I think that most cities would give their right arm to have 96 acres in a downtown to be used as a really powerful part of the cityscape. And the HemisFair is a long way from being that.”

Wagner was on the planning staff for HemisFair decades ago, and today she is one of the organizers trying to renovate the Women’s Pavilion—one of the few fair structures built as a permanent building. This renovation, she says, could be a “catalyst project” that would ignite renewed interest in HemisFair Park. She hopes the anniversary celebrations and the yearlong special exhibit at the ITC also will help spark public interest in revitalizing the park property.

The 2,000-square-foot exhibit at the ITC includes videos, photographs, memorabilia, costumes worn during the fair (including a rare Pucci-designed minidress), as well as a section on the families whose homes were demolished to make room for the fair.

“I hope that [visitors] will be delivered some information about why the HemisFair was attempted and achieved and what effect it had on San Antonio and Texas,” says John L. Davis, ITC interim executive director. During the fair, Davis was on the ITC research staff and worked most days on the Texas exhibit inside the Texas State Exhibits Pavilion.

“We’re hoping we will raise some questions with those visiting about what happens when you do urban renewal projects,” Davis says. “We’d like to raise questions about why people participate in world fairs. Is it used for economic advancement? Does it have an effect on our understanding of other people? And ultimately from all of this, we hope that people will also learn something about themselves.”

The ITC called the special exhibit San Antonio’s Introduction to the World because, Davis says, “at this time San Antonio was considered to be a relatively small town, undeveloped economically and with a large military base. And a world’s fair would deliberately bring San Antonio to the attention of not only the Americas but the world.”

At the same time, with the arrival of visitors and exhibitors from abroad, San Antonio came to learn about other cultures and people.

“I don’t think people in San Antonio had been exposed to Japan and China and Guatemala and some of these other countries,” says Shirley Mock, senior research associate at the ITC. Mock led the research team charged with piecing together the HemisFair exhibit.

“[These countries] were actually there presenting their culture. And it wasn’t just a token cultural presentation. I think part of our Folklife Festival and our Asian Festival come out of that tradition, that excitement of seeing and actually participating in these cultures.”

The annual Folklife Festival that takes place at the ITC began in 1971. The Asian Festival, also celebrated at the ITC, started in 1977.

Growth of the City

Aside from this legacy of festivals and cultural celebrations, the HemisFair leaders argue that the fair set the stage for San Antonio’s explosive population growth and economic expansion.

“You are living today at this very moment on what was done in 1968,” says Tom C. Frost Jr., whose Frost National Bank contributed $170,000 toward the HemisFair event. “Two of the largest sources of employment in San Antonio for the past 40 years have been tourism and health care. It was 1968 when HemisFair opened in April. And it was in 1968 that we opened the Medical Center. And our two largest payrolls in San Antonio today are still in tourism and health care.”

Frost says San Antonio would have had a more difficult time recruiting corporations such as Southwestern Bell [now AT&T] and Toyota if HemisFair hadn’t “put San Antonio on everybody’s radar screen.”

But UTSA history professor David Johnson argues that many other economic development efforts taking place at the same time played larger roles than the world’s fair. “The importance of HemisFair is its psychological impact on the local business community and business social elite in the city,” says Johnson, who is currently writing a book that explores San Antonio’s 20th century political history.

“This wasn’t the very first time they tried to do something to promote the city’s development,” he says. “But it was a spectacular event in their minds. The impact of the activity level and cooperation to do something of that scale is that it leaves this enduring sense of accomplishment and pride.”

Decades before HemisFair, various forces had been working to make things happen in the city, but without great success. An attempt to hold Texas’ centennial state celebration saw San Antonio take runner-up to Dallas, which held the celebration in 1936. At the same time, an attempt to bring a medical teaching university to San Antonio failed, and instead, the Southwestern Medical School—now the Southwestern Medical Center—opened in Dallas in 1943.

San Antonio saw some success with the construction of the River Walk as a Works Progress Administration project from 1939 to 1941, but it didn’t become a major attraction until after commercial revitalization began in the 1960s.

“What I see is different groups of people working on different projects for their own particular reasons and nothing that crosses boundaries between the groups,” Johnson says. “And this thing with the HemisFair sort of got dropped in the middle of this stuff and it becomes the big public event that has immediate visibility and it looks like it had immediate impact.”

The decades-long efforts to bring a medical school and a public university to San Antonio, as well as the efforts to improve the River Walk, Johnson says, bore fruit during the late 1960s and may have played a more significant role in San Antonio’s growth and development during the following decades than HemisFair did.

While San Antonio Mayor Phil Hardberger agrees that HemisFair was not an economic driver for the city, he says it served as a recruiting tool during the 1960s and 1970s. Hardberger himself says that he and his wife decided to move to San Antonio from Odessa after attending the fair.

“We stayed in La Mansión [del Rio Hotel] and that gave us a great impression. We went to the HemisFair and afterward we said, ‘Let’s make San Antonio our home,’” Hardberger says.

The fair, the work required to put on such an event, and the construction that took place gave Hardberger the impression that San Antonio was “a city of the future,” with “growth potential—intellectual, economic, and population growth.” Hardberger says that revitalizing the HemisFair Park area is a “fairly vast” project that would take many years, more than the year that he has left in office. But he says he would like to begin serious conversations about doing so.

“The true value of the fair is that it changed the ethos of San Antonio—the way we thought and our outlook on the rest of the world,” Hardberger says. “And that’s the real value.”