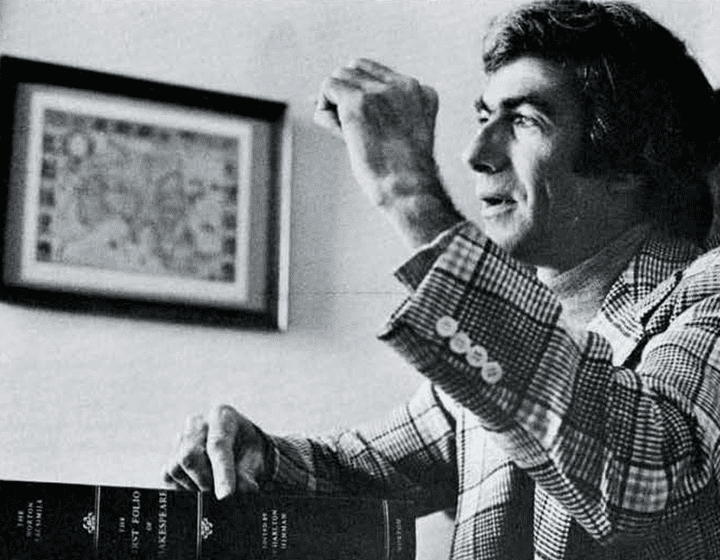

Division Chair Alan Craven describes how UTSA teaches English literature classics in an innovative context.

Innovative English

UTSA’s program educates through both traditional and inventive courses

[ This article was originally published in the UTSA newsletter The Discourse in October 1975 ]

Like Janus, the mythical two-faced creature who used one face to look backward and one face to look forward, UTSA’s Division of English, Classics, and Philosophy emphasizes both traditional and innovative approaches to literature.

The traditional includes such courses as Homer and the Tragic Vision, Shakespeare: The Early Plays, Advanced Composition, and The Romantic Poets. At the opposite end of the curriculum are courses that focus on the portrayal of women in literature, the comedy of ancient Greece and Rome, the evolution of black literature and heroes in fiction.

“We’re making the old more relevant by focusing on the classics in an innovative context,” says Alan Craven, director of the division.

English is traditionally the heaviest area for elective enrollments in American colleges and universities, Craven observed. “We want to develop courses not just for English majors but for students with a diversity of interests,” he says.

Women in Literature, a course taught by Mary Kelly, exemplifies this intent. The course investigates the image of women in poetry, novels, and plays from the Middle Ages to the present. According to Kelly, both male and female novelists have focused on different aspects of womanhood. Their books reflect the cultural role accorded to women and also reveal their own unexamined assumptions about women.

Students are also getting a new perspective in Duane Conley’s class. Titled The Comic Experience, the course is serious business, although a chuckle is permitted from time to time. Conley’s class reveals that theatergoers in ancient Greece were rolling in the aisles at the same kind of humor people laugh at today. Peter Sellers’ comedy mix-ups and Lucille Ball’s backfiring schemes had their origin more than 2,000 years ago.

According to Conley, Aristophanes, whose plays are the oldest surviving major comic works in European literature, used word play, absurd plots, political satire, and “raw humor” in his comedies. His Lysistrata was performed in 411 B.C. The plot, a sex strike by wives of warring Athenian and Spartan troops to make them stop fighting, has been parodied in many modern stories and plays.

A course called Black Literature has also been introduced at UTSA this fall. The course is conducted by Arnold Sparks. Although novels by black writers such as Frank Yerby had been published, literature dealing with the black culture as a shared human experience was excluded from most anthologies until the mid 1960s, Sparks’ class has learned.

Black literature is not necessarily by black writers nor about black people. Sparks defines black literature as “a composition that develops a theoretical definition of the black culture.”

The students are exposed to works by such authors as Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, and Jean Toomer—all men who became a “watershed of black literary endeavor in America” during the early ’20s. They formed the core of what was later called the Harlem Renaissance, Sparks related.

Literature projecting different value concepts, The Hero in Fiction, is an English course taught by Elizabeth Heine. She believes that heroes are important as symbols of high ideals. “The adversary may be something physical, like the shark in Jaws, or it may take the form of a test of ideals or values, as in resisting temptation,” she explains. “Heroes and heroic values differ from culture to culture and from generation to generation. However, some heroic characteristics endure. We still value the one who puts others before self in times of need.”

The newest form of hero in literature is the antihero. Heine explains, “He’s the ordinary man who is trying to cope with everyday life. He finds his values in private ways.”

UTSA’s progressive courses prepare English degree students for teaching careers and for many professional positions outside the teaching field, Craven relates. “Because of UTSA’s multidisciplinary emphasis, we are able to bring together related fields of study within a single division,” he says. “English, classics, philosophy, and the humanities have been brought together in the English division to help the student acquire a broader vision of human experience.”