Forever Young

Forever Young

FROM THE WINTER/SPRING 2019 ISSUE

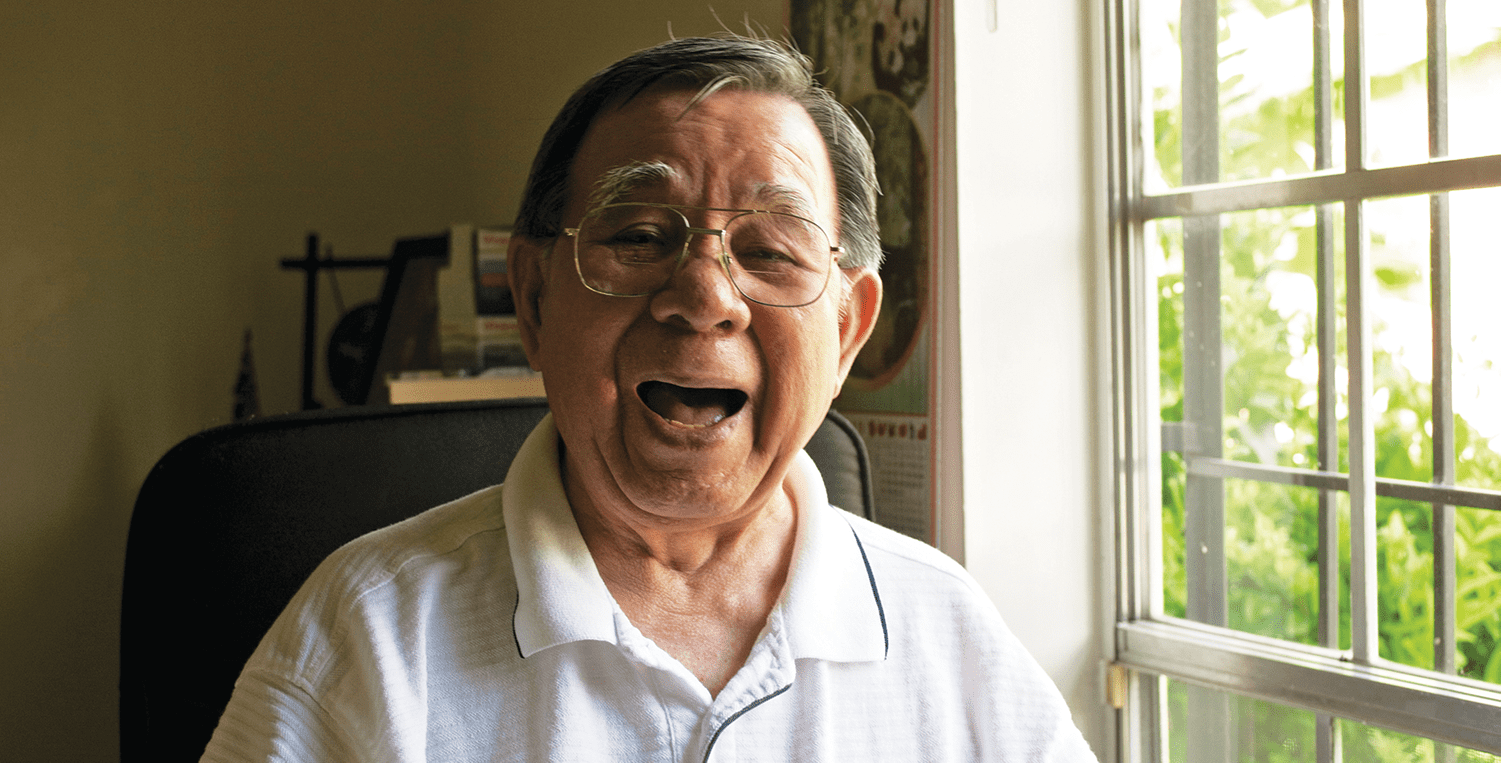

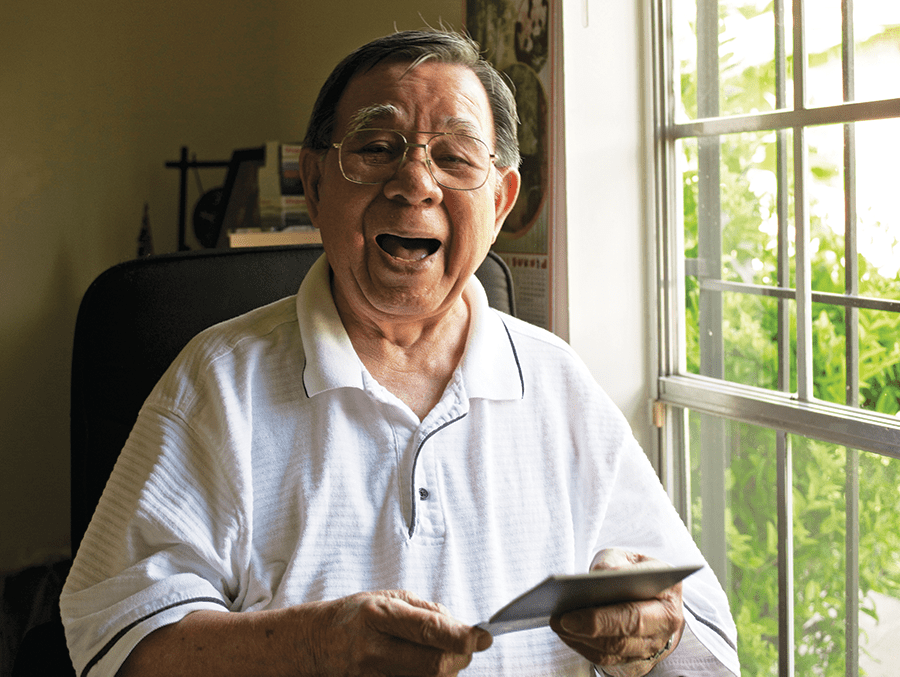

Paul Kattapong M.A. ’79 knows the secrets to a long life: First, have oily skin. It makes your face look younger. Second, wash your hands constantly to keep germs away. And finally, laugh often. When he originally shared these insights for an interview with Sombrilla Magazine in 2010, Kattapong was 93 years old and said he was hanging his hopes on these three things to get him to 100. “I will try my best to live to 100 years old,” he said. “Once I get there, I will join the centennial crowd. After that, I will try my best to get to the supercentennial. I keep my fingers crossed.”

“I finally finished my 36-hour requirement, but it was very rough, those four years.”

His own advice has served him well. Now 101, despite arthritis, gout, and swollen legs that require him to use a walker, Kattapong boasted that his doctors estimate he’d make it to 109. “I hope that is true.”

Kattapong is UTSA’s oldest living alum. And decades after receiving his master’s degree in bicultural-bilingual studies, he remembered how difficult—but worthwhile—it was to complete his degree.

“Those four years were really tough,” he said. “I came home after 5 p.m., sat down in my chair, and would catnap for five to 10 minutes before I would get up and go to my evening class. I finally finished my 36-hour requirement, but it was very rough, those four years.”

But nothing in Kattapong’s life has come easy. He was born in 1917 in Bangkok, Thailand, to Chinese parents. When he was 6 years old, he began attending school— first learning Chinese, then Thai—before studying English. When he was in seventh grade, his father died, and so did Kattapong’s guaranteed education. Unlike the United States, where all students can attend public school at no cost, Thailand required students to pay tuition. Without his father’s income to pay for school, Kattapong was faced with a choice: quit school or work for it.

He began cleaning classrooms to pay for his education. “From seventh grade until I left Bangkok, I had no money from my parents,” he says. “I had to earn it for myself.”

He finished high school and then attended college in Bangkok. During World War II he became a member of an underground movement fighting alongside American forces. After the war, he says, he received a scholarship to attend George Williams College in Chicago, where he majored in group work education. In 1954 he met and married his wife, Verna Anna Voth.

After graduating from college Kattapong got a job with the Department of Defense in Monterey, Calif., teaching Thai. Over the next 32 years he continued working with the government, rising in rank from language instructor to specialist to supervisor.

“Education helped me a lot.”

Kattapong credits his mother, Maasii, for the route his life has taken. Though she never went to school or learned to read or write, she pushed for Kattapong to finish school at whatever cost. It’s a message he’s passed down to his children and grandchildren. “One day my mother was sick,” he says. “She told me to study hard, complete your education and graduation, and stand tall in your community, raise your father’s family flag up in the sky. I never forgot that.”

“Education helped me a lot,” he says. “If I had never heard my mother’s words to remind me and encourage me to pursue an education, I would never have had the chance to come to the U.S. I would never have had the chance to finish my college education and all of my children to get through their education.”