Boomtown, Texas

Carrizo Springs busting at the seams

The once-sleepy Carrizo Springs is now awakening with extraordinary and sudden economic growth. UTSA is lending its hand to aid this community unprepared for economic surge.

The result of microscopic plants and animals that lived in a huge, shallow ocean that covered Texas some 92 million years ago is now clearly visible from the dark reaches of outer space. From miles above the earth, the picture of a crescent-shaped 400-mile-long, 50-mile-wide scab of light extending across a swath of South Texas just south of San Antonio rivals the lights emanating from the state’s major metropolitan centers.

The source of that light, more than 220 derricks drilling for oil across 20 counties 24 hours a day, is more than just startlingly eye-catching. That picture may be the ultimate snapshot of the state’s energy future and represents what is being referred to as the single biggest economic development in Texas history—and UTSA is involved in helping the area, known as the Eagle Ford Shale, assess the changes and capitalize on the boom.

It took a long time for this overnight bonanza. Over millions of years, the microscopic life that absorbed energy from the sun and stored it as carbon molecules accumulated in layers of sediment at the bottom of the shallow sea that once covered the region. The biomass was created when the plants and animals died and sank to the sea bottom.

There the residue remained, trapped for eons under incredible pressure and heat surrounded by what until very recently had been impenetrable rock formations. But this year alone, about $30 billion will be spent pulling black gold from this formerly resistant land.

It is not only the drilling, pipeline and trucking firms that stand to gain from what was once a lightly populated, mostly economically depressed part of rural Texas.

Business owners anywhere near the huge play have seen their companies change almost overnight, with the level of activity redefining what an oil industry hotbed is. Last year, oil exploration and extraction accounted for a regional economic impact that surpassed $61 billion, according to a UTSA economic analysis.

The Eagle Ford Shale formation is estimated to hold billions of barrels of crude oil, untold trillions of cubic feet of natural gas and other petroleum products trapped under huge layers of rock.

Experts believe the volume is so huge and the find so significant that they predict that by 2020 the United States will have surpassed Saudi Arabia as the world’s premier energy exporter, due partly to the drilling now ongoing in South Texas.

The more than 800 oil derricks operating all over Texas this summer represented nearly half of all U.S. rigs and nearly 25 percent of rigs drilling around the world.

In the Eagle Ford, the twinkling lights seen from satellites represent the contemporary equivalent of the boom of the 1800s Gold Rush.

Except bigger, much bigger.

Based on capital expenditures alone, the activity at Eagle Ford Shale ranks as the largest single oil and gas development in the world.

Last year, oil exploration and extraction was responsible for more than 116,000 jobs, said Thomas Tunstall, who heads the UTSA Institute for Economic Development’s Center for Community and Business Research.

But the institute’s findings, along with an earlier study tracking the activity’s impact in specific counties where drilling is active, also point to potential problems for exploration firms and the host of related businesses that support them, as well as for landowners, local governments and residents.

The huge amounts of water needed for exploration and extraction of the oil and gas, the traffic generated as a result of that activity by fleets of 18-wheel tractor trailers, and the skyrocketing housing prices fueled by a huge influx of workers scrambling for places to live all create formidable issues for many of the small towns in the region. And many of them appear to be poorly positioned to manage the massive infrastructure needs the boom is causing.

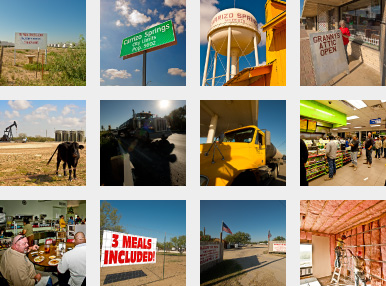

Over the next decade as drilling ramps The modern-day black gold rush has resulted in numerous so-called “man camps” that temporarily house oil field workers. This one, called Mesquite Lodge, also has a cafeteria, entertainment room, theater and clinic. Oil companies provide transportation between the camps to the fields. Local restaurants, such as Red Dog’s, are benefitting from the influx of traffic in the area. The lunch-rush often brings Juan Carmona, Dimmitt county commissioner, and many other locals to Balia’s Restaurant. New construction projects are sprouting up in and around Carrizo Springs, where the population has jumped from 5,400 to more than 40,000 in one year. up, some of those issues will increase in complexity for local governments unequipped to address them, despite the huge amounts of “new” revenue coming to cities and counties in the region, Tunstall said.

The modern-day black gold rush has resulted in numerous so-called “man camps” that temporarily house oil field workers. This one, called Mesquite Lodge, also has a cafeteria, entertainment room, theater and clinic. Oil companies provide transportation between the camps to the fields.

The university’s effort focuses on measuring the economic and social impact the massive exploration effort is having on 14 rural South Texas counties most significantly affected by the drilling but which have little existing infrastructure support, he noted.

“Now our community, and many others like it, stand to benefit from the huge increase in drilling activity,” and the accompanying increase in the tax base, said Adrian DeLeon, mayor of Carrizo Springs, a community that now is called home by more than 40,000 people. Just last year, the population was around 5,400.

“We have a great opportunity to get some capital improvement projects that we would not otherwise even dream of being able to fund,” said the first-time mayor, who along with his mother runs two restaurants that rely heavily on the daily traffic generated by the oil firms.

“But at the same time, many of our communities don’t have a planning department or even a city engineer, so coordinating the growth and trying to plan for smart growth is a real challenge for us,” he said.

That is where much of the university’s community outreach effort is focused, said Francine Romero, associate dean in the College of Public Policy.

A component of UTSA’s involvement is a partnership with Shell Oil that provides direct university expertise to elected officials and the region’s policy makers, she noted.

A series of public meetings—including one in DeLeon’s hometown and ending with a session in San Antonio with local elected officials and industry representatives—was designed to help governments respond to the massive influx of people, equipment and economic activity to an area that has traditionally been lacking in growth opportunities.

For local and county governments, the increased tax revenues are swelling local coffers, Romero noted. In the three years ending in 2012, sales tax collections in the targeted area rose a whopping 68 percent, from $751 million to $1.2 billion.

In 2012, the last year for which full data is available, construction activity accounted for nearly $40 million in direct and indirect economic impact, generating 279 new jobs with a payroll of $11.4 million.

But while the economic impact on rural, impoverished counties is important, “to me it is about government structure being in place to be able to formulate good policy and good decisions. It is about helping people build up the capacity of their local government to a level that they need to take maximum advantage of the boom they are experiencing,” said Romero.

In addition to meeting “livability issues,” communities also face critical housing concerns. DeLeon said many residents in Carrizo Springs are being forced out as the demand created by the oil field crews causes local rental rates to rise sharply.

“Some [fast-food restaurant] workers are pulling down $15 an hour and getting a $500 signing bonus for staying on the job six months,” Tunstall said, illustrating how desperate some business owners are to hold onto their workers.

“But at the same time, a house that was renting for $500 to $600 is now going for $2,500, if you can even find one vacant. That kind of rent in South Texas was just unthinkable three years ago, so there are two quite contrasting sides to the boom,” he said.

Increased tax bases will give local governments the opportunity to build more parks and green spaces to improve quality of life. The money may also lead to improved medical facilities, improved roadways and more adequate power and water supplies. The increased population also has the potential to help local school districts boost the quality of K-12 education as well as vocational education programs, Tunstall pointed out.

But he noted that these communities must also look to the future. “There is another side to the boom, not what the communities are going through right now, but what they will look like 20 years from now, what sort of growth there will be and how best we can assist the cities and the region to best manage now what their community will look like then,” he noted.

The opportunity looms.

“There is a huge opportunity for all concerned,” Tunstall said. “Right now we have the chance to leverage the academic side and provide the expertise available here to be able to provide real advice to policy makers, elected officials and business leaders for the future benefit for all.”